A van moves steadily through the city streets, braking smoothly when another vehicle abruptly enters its lane. However, its steering wheel turns by itself, with no one occupying the driver’s seat, reports AP.

Nissan Motor Corp.’s driverless technology, incorporating 14 cameras, nine radars, and six LiDar sensors installed in and around the vehicle, underscores Japan’s determination to catch up with leaders like Google’s Waymo, which has pioneered the field in the U.S.

Despite being home to some of the world’s top automakers, Japan has lagged behind in the global transition to autonomous driving, a sector currently dominated by China and the U.S. However, progress is accelerating.

Waymo is set to debut in Japan this year. While details remain undisclosed, it has partnered with major taxi operator Nihon Kotsu, which will supervise and manage its all-electric Jaguar I-PACE sport-utility vehicles in the Tokyo area, initially with a human cab driver on board.

During Nissan’s demonstration, the streets teemed with vehicles and pedestrians. The van maintained the area’s maximum speed limit of 40 kph (25 mph), with its destination pre-set via a smartphone app.

Takeshi Kimura, an engineer at Nissan’s Mobility and AI Laboratory, asserts that automakers have a greater capability to integrate self-driving technology into a vehicle’s overall functionality, as they possess a deeper understanding of cars.

“How sensors must be adapted to a vehicle’s movements, as well as monitoring them and the computing system to ensure reliability and safety, requires comprehensive knowledge of the automotive system,” he explained during a recent demonstration, in which reporters took a short ride.

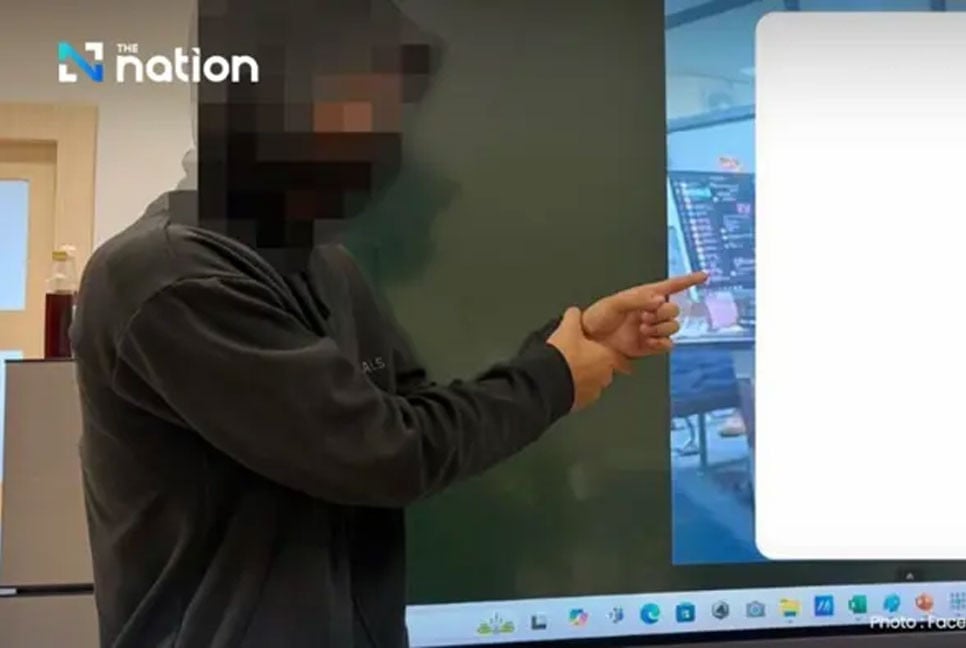

Nissan’s technology, currently being tested on its Serena minivan, remains at Level Two within the industry’s classification. A person stationed at a remote-control panel in a separate location—Nissan’s headquarters, in this case—is prepared to intervene should the system fail.

Additionally, a human is seated in the front passenger seat during test rides, ready to assume control if necessary. However, under normal conditions, both the remote operator and passenger do not engage in driving.

Nissan intends to deploy 20 such vehicles in the Yokohama area over the next few years, aiming to achieve Level Four autonomy—meaning complete independence from human intervention—by 2029 or 2030.

Autonomous vehicles could address Japan’s growing challenges, particularly a shrinking population and a shortage of drivers.

Several other companies are also developing this technology in Japan, including startups like Tier IV, which is promoting an open-source collaboration on autonomous driving.

Currently, Japan has approved the use of Level Four autonomous vehicles in a rural area of Fukui Prefecture, though these resemble golf carts more than actual cars. A Level Four bus is in operation within a restricted area near Tokyo’s Haneda Airport, but it has a maximum speed of just 12 kph (7.5 mph). In contrast, Nissan’s autonomous vehicle functions as a fully operational car, equipped with standard mechanical features and capable of normal speeds.

Toyota Motor Corp. has also introduced its own “city” or residential area near Mount Fuji, designed specifically to test advanced technologies, including autonomous driving.

Progress in this field has been cautious.

University of Tokyo Professor Takeo Igarashi, an expert in computer and information technology, believes significant challenges remain, as accidents involving driverless vehicles tend to evoke greater concern than conventional crashes.

“With human-driven cars, responsibility is clear—the driver is accountable. But with driverless vehicles, there is uncertainty over who bears responsibility,” Igarashi told The Associated Press.

“In Japan, the standards for commercial services are exceptionally high. Customers expect absolute perfection, whether in restaurants, taxi services, or any other industry. Since autonomous driving is considered a service, even the smallest mistake is deemed unacceptable.”

Nissan insists its technology is safe. Unlike a human driver, who can only look in one direction at a time, a driverless car continuously monitors its surroundings with an array of sensors.

During the recent demonstration, when a system failure occurred, the vehicle simply halted, ensuring safety.

Phil Koopman, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, notes that the autonomous vehicle industry is still in its early stages.

A major challenge is addressing “edge cases”—rare but potentially hazardous situations that the system has not yet been trained to handle. Large-scale autonomous fleets must operate for an extended period before such scenarios can be fully accounted for, he explained.

“Each city will require dedicated engineering efforts and the establishment of a specialised remote support centre. The deployment process will continue city by city for many years,” Koopman said.

“There is no magic switch.”

Source: AP

bd-pratidin