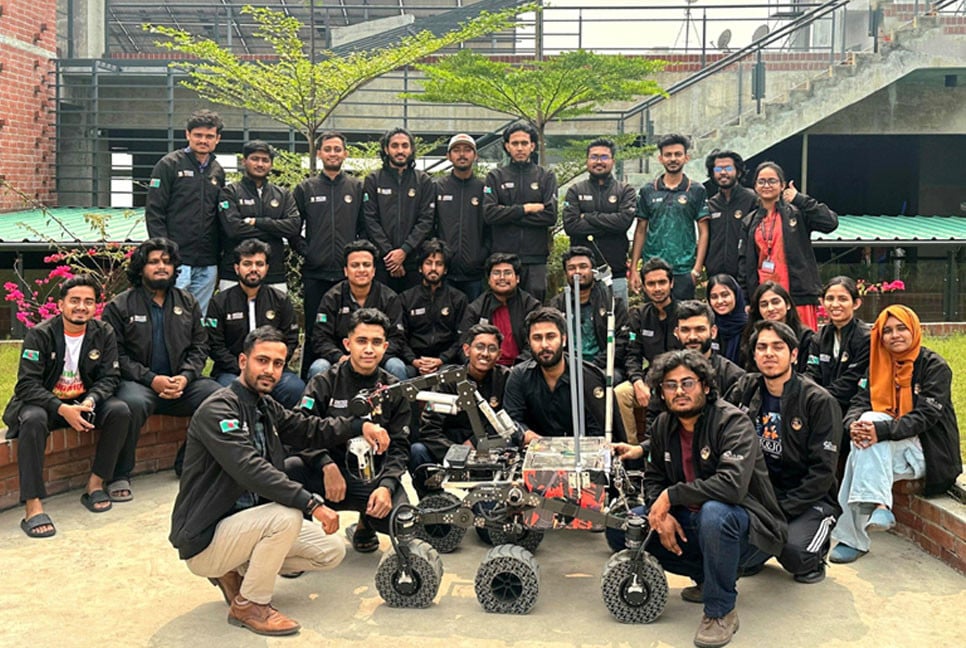

In January 2024, Noland Arbaugh, a 30-year-old man paralyzed for eight years, became the first person to receive a brain chip from Neuralink, the neurotechnology company founded by Elon Musk.

Despite understanding the risks, Noland emphasized that the focus should be on the science rather than on him or Musk.

He expressed that, regardless of the outcome, he hoped to contribute to the advancement of the technology, acknowledging that any failures would provide valuable insights for future improvements.

'This shouldn't be possible'

Noland Arbaugh, paralyzed below the shoulders in a 2016 diving accident, feared he might never regain independence.

In 2024, he became the first person to receive a Neuralink brain chip, which allows him to control a computer with his mind.

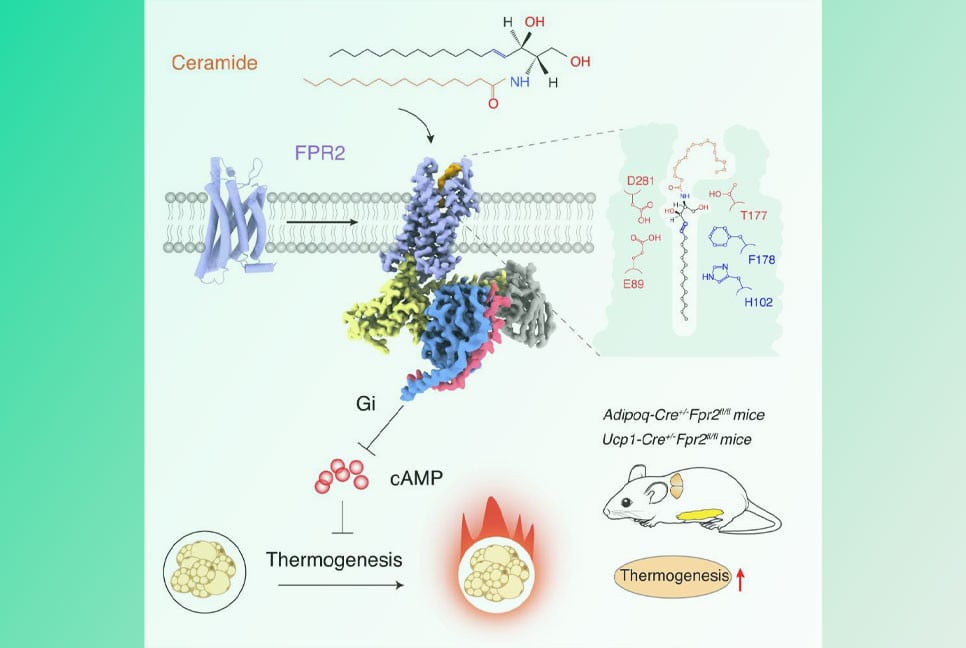

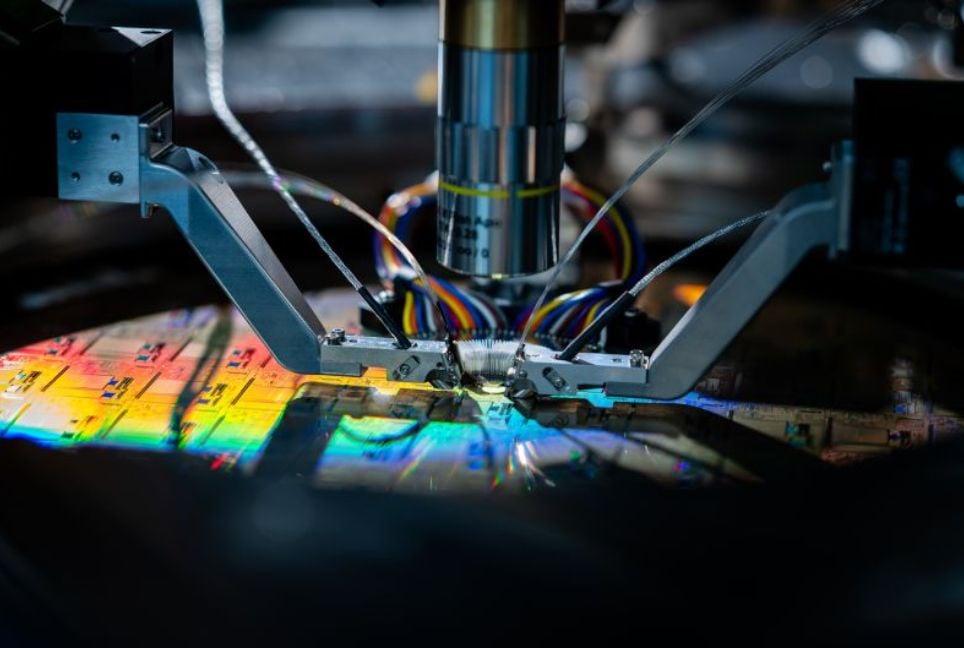

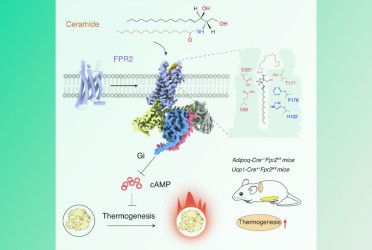

This brain-computer interface (BCI) detects electrical impulses from the brain and translates them into digital commands.

While Neuralink, backed by Elon Musk, has attracted attention and investment, experts warn that the technology’s long-term effects are still unknown.

Despite the controversy, the chip has significantly improved Noland’s life, restoring some independence and hope for the future.

'No control, no privacy'

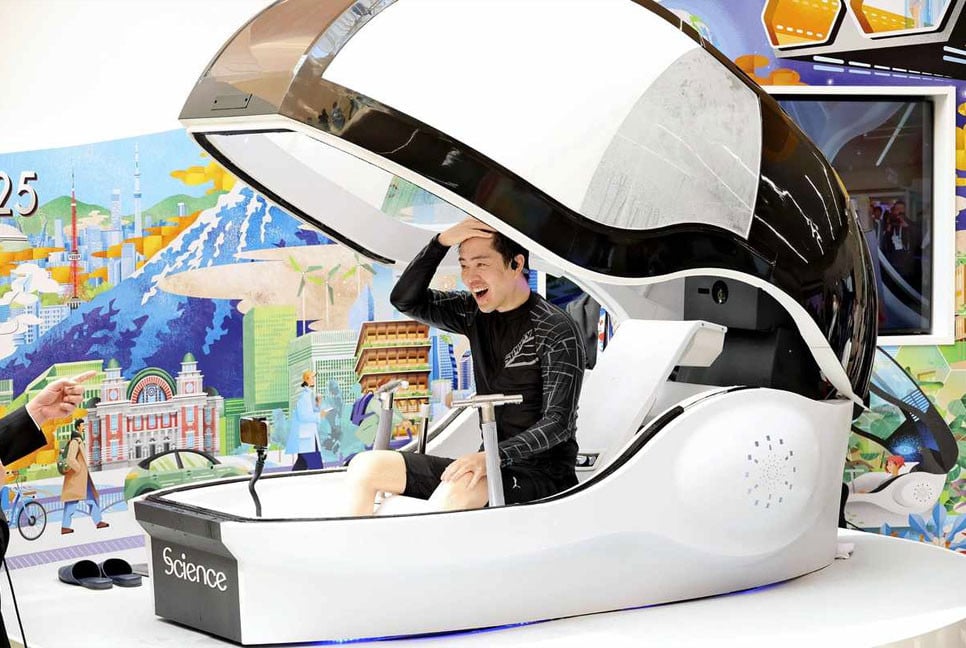

When Noland awoke from the surgery which installed the device, he said he was initially able to control a cursor on a screen by thinking about wiggling his fingers.

"Honestly I didn't know what to expect - it sounds so sci-fi," he said.

But after seeing his neurons spike on a screen - all the while surrounded by excited Neuralink employees - he said "it all sort of sunk in" that he could control his computer with just his thoughts.

And - even better - over time his ability to use the implant has grown to the point he can now play chess and video games.

"I grew up playing games," he said - adding it was something he "had to let go of" when he became disabled.

"Now I'm beating my friends at games, which really shouldn't be possible but it is."

Noland is a powerful demonstration of the tech's potential to change lives - but there may be drawbacks too.

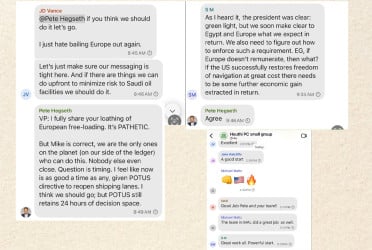

"One of the main problems is privacy," said Anil Seth, Professor of Neuroscience, University of Sussex.

"So if we are exporting our brain activity [...] then we are kind of allowing access to not just what we do but potentially what we think, what we believe and what we feel," he told the BBC.

"Once you've got access to stuff inside your head, there really is no other barrier to personal privacy left."

But these aren't concerns for Noland - instead he wants to see the chips go further in terms of what they can do.

He told the BBC he hoped the device could eventually allow him to control his wheelchair, or even a futuristic humanoid robot.

Even with the tech in its current, more limited state, it hasn't all been smooth sailing though.

At one point, an issue with the device caused him to lose control of his computer altogether, when it partially disconnected from his brain.

"That was really upsetting to say the least," he said.

"I didn't know if I would be able to use Neuralink ever again."

The connection was repaired - and subsequently improved - when engineers adjusted the software, but it highlighted a concern frequently voiced by experts over the technology's limitations.

Big business

Neuralink is not the only company exploring brain technology. Synchron's Stentrode device, designed for people with motor neurone disease, offers a less invasive option. Installed through the jugular vein and moved to the brain via a blood vessel, it connects to the motor region, allowing users to control devices by thinking.

Currently used by 10 people, one user even controls Apple's Vision Pro headset, enabling virtual experiences like visiting far-off locations.

While Noland's Neuralink chip is part of a six-year study with an uncertain future, he believes his experience is just the beginning of what could revolutionize paralysis treatment and brain research.

Source: BBC

Bd-pratidin English/ Afia