On Tuesday (January 28), rail communication across the country was completely disrupted as railway workers, citing various demands, declared an indefinite halt to train operations. They expressed frustration, saying that they had been repeatedly assured that their demands would be addressed, but those promises had not been fulfilled. Faced with no other option, they decided to take drastic action. The sudden suspension of rail services caused immense inconvenience to millions, plunging daily life into chaos and leaving many stranded.

In response, the adviser in charge of the Ministry of Railways visited Kamalapur Station in person, attempting to address the situation. He asserted his authority, urged the workers to call off the strike, and warned of potential actions if the disruption continued. However, his efforts proved ineffective. Later that evening, a meeting between the adviser and the protest leaders ended in failure, deepening the uncertainty surrounding the situation.

Amid this crisis, with the country’s largest transportation system paralyzed, BNP leader Shimul Biswas intervened. He took the initiative to engage in direct talks with the railway workers, and after productive discussions, the deadlock was finally broken. As a result, rail services resumed on Wednesday (January 29), bringing relief to the public.

This episode highlights a key distinction: while bureaucrats and intellectuals often complicate matters by relying on authority and rigid solutions, politicians, through dialogue and negotiation, can resolve conflicts more effectively.

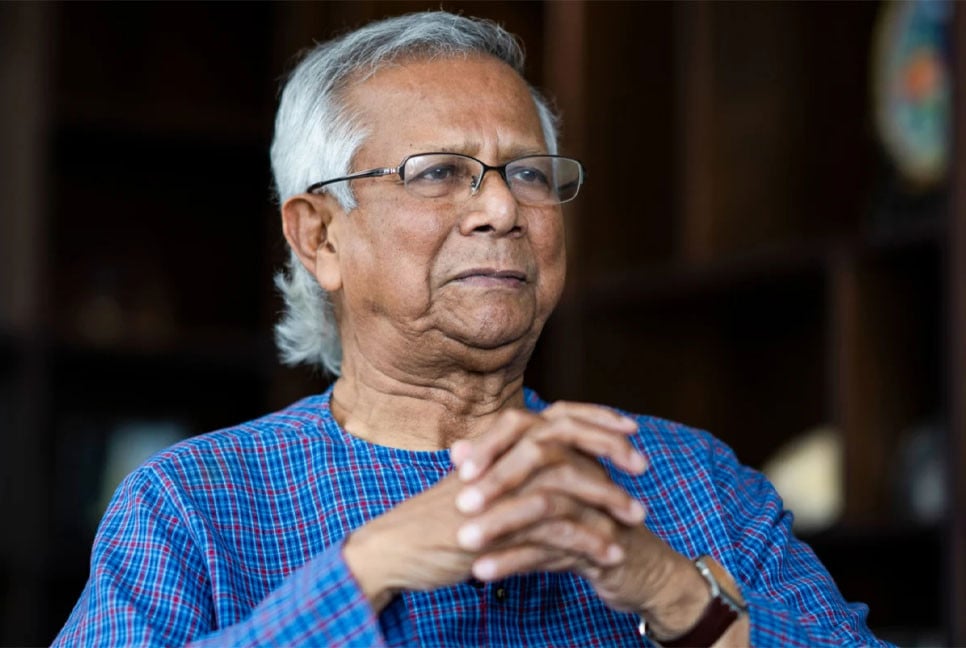

For almost six months, the country has been under the leadership of civil society, and numerous issues have been emarging each day. During this period, 136 movements have taken place, driven by various logical and illogical demands. However, the Interim Government, led by Prof Muhammad Yunus, has demonstrated a sense of rigidity and ineptitude in addressing these issues.

A recent example of this is the railway strike. Yet, the strike proved that political wisdom and prudence could easily resolve such issues, a lesson demonstrated by BNP leader Shimul Biswas. This incident underscores one important truth: governing the country is, in fact, the responsibility of politicians.

On August 8, after Sheikh Hasina's departure on August 05, an Interim Government was formed under the leadership of Prof Muhammad Yunus, symbolizing the hopes and aspirations of the people. The fall of the autocratic government was made possible by 13 years of political struggle and the fearless student movements in the last 36 days. This led many to believe that under Prof Yunus’s leadership, a new Bangladesh would emerge—one of equality, unity, and youthful energy, embarking on a new journey. However, as time passes, the road ahead has become increasingly difficult, and the pain of shattered hopes is turning into deep sighs of disappointment.

What is the underlying cause of this situation? To understand, it is crucial to analyze the structure of the Interim Government. The government includes only three student representatives, while the majority of the advisors are civil society figures, working in NGOs and development organizations. This has led some to sarcastically refer to the government as the "NGO government." A key weakness of the Interim Government is that, with a few exceptions, most members of the advisory council were not directly involved in the movement. They observed the protests from a safe distance, and had the movement not resulted in the fall of Sheikh Hasina, they would not have faced any personal repercussions. As a result, these advisory council members are unable to fully reflect the aspirations of the people, nor can they effectively cultivate the revolutionary spirit and ideals that the movement represented. This has led to the government's consistent failure to meet the expectations of the public. Daily, new crises are emerging, protests are being held over various demands, and a sense of instability is growing throughout society.

However, upon closer analysis, it becomes evident that many of these crises could have been resolved at their inception. Take, for instance, the recent protests by students from the Seven Colleges. This movement could have been concluded much earlier. During the Awami League’s tenure, the students became unwitting victims of a personal dispute between two pro-Awami League professors: the then Vice-Chancellor of Dhaka University, AAMS Arefin Siddique, and the Vice-Chancellor of the National University, Harun Or Rashid. While the Interim Government has reversed many of the previous administration’s decisions, it has failed to take any action on this matter.

The Interim Government's education adviser, Wahiduddin Mahmud, is undeniably an intellectual, wise, and respected figure. However, there is growing concern over his ability to effectively execute his responsibilities within the ministry. His response to the ongoing crisis has been marked by indifference and neglect. Rather than addressing the issue directly, he has sought theoretical solutions in his characteristic intellectual manner, placing excessive reliance on bureaucrats. Consequently, the problem has spiraled into widespread unrest. Similarly, the textbook crisis has been mishandled, compounding the issue. Daily reports of such failures are emerging from various ministries. In one instance, an adviser reportedly told primary school teachers, "If you are dissatisfied, look for another job." Can such a response be deemed appropriate from a leader responsible for the welfare of the people?

Public frustration is mounting, and the need for political intervention to resolve these crises is becoming increasingly urgent. The recent railway workers' strike serves as a prime example. Had Shimul Biswas not intervened, the resolution would not have come as swiftly. This episode has made one thing clear: there is no substitute for an elected government to lead Bangladesh forward. For over a decade, the country has been without an elected government, leaving the people disenfranchised. Yet, when the topic of elections arises, why do some civil society advisors in this unelected government react with such aversion? That is a question only they can answer. However, despite forming a government with widespread initial support, this administration is rapidly losing public confidence—a pattern that is not new.

In Bangladesh, civil society has repeatedly proven to be ineffective in governing the country. The question of why civil society fails in governance could be the subject of extensive research. If we look at the events of 1/11, for instance, during the period of intense conflict, an Interim Government was formed with military support. The primary responsibility of that government was to quickly create an environment for a credible election and to transfer power to the elected representatives. However, instead of focusing on this task, the 1/11 government became involved in an agenda of de-politicization. It launched a campaign to discredit businessmen, industrialists, and politicians. Not only that, but the government also made strenuous efforts to form a "king’s party" while in power, leading to a loss of public trust in Dr. Fakhruddin’s administration. This is why the civil society-led government ultimately failed. The entire control of the 1/11 government was in the hands of intellectuals who were aligned with the "Prothom Alo" and "Daily Star" media groups. Democracy was not their agenda; instead, they aimed for de-politicization and prolonged power.

If we examine the advisers of this Interim Government more closely, we will find that a significant portion of them are individuals whose primary identity is that they regularly write columns for "Prothom Alo" and "Daily Star." Beyond that, they have made little significant contribution in recent times. It is undeniable that these individuals are the sponsors and advocates of the de-politicization theory promoted by "Prothom Alo" and "Daily Star". Many believe that this is why the country's problems are deepening.

Civil society in Bangladesh will not succeed until its members work selflessly and impartially, motivated by patriotism and a genuine desire to serve the country. The current government’s sole task is to return power to the people. However, if civil society members, without accountability to the people, return to the streets to push their old agenda, their fate will be the same as that of the 1/11 government.

Governing the state is the responsibility of politicians. It is a task that should be carried out by them alone. Every profession has its own specific duties and scope. When someone steps outside their designated role, it rarely leads to positive outcomes. This has been proven during the 15 years of Awami League rule. During this time, corrupt individuals, sycophants, and criminals rose to political power. The Awami League's 15-year rule attempted to dismantle all political institutions. In their pursuit of disbanding all political parties, they themselves have now become politically irrelevant.

Under the Awami League’s rule, certain police officers grew more powerful than even the party leaders, while bureaucrats became known as “Awami bureaucrats.” This created a state of disorder across the country, with power-hungry individuals from various professions, driven by personal gain, encroaching on the corridors of power. As a result, the country became politically void. The 2014 and 2018 elections serve as stark evidence of this.

Exceeding limits leads to severe consequences. Everyone must stay within their designated role. People should perform the duties they are entrusted with. Recently, BNP's Acting Chairman Tarique Rahman called on everyone to learn from August 5. The biggest lesson is that clinging to power forcibly leads to disastrous outcomes. Those who go too far always face negative consequences.

Bangladesh's civil society holds a historic responsibility. They are the conscience of the nation, the voice of the people. They should guide the nation, distinguishing between right and wrong, and offer advice and support to politicians to ensure the country stays on the right path. However, if they step into the political arena themselves, seeking permanent control over governance, it will not be feasible. This was clearly evident during the events of 1/11, where such an approach ultimately proved to be ineffective.

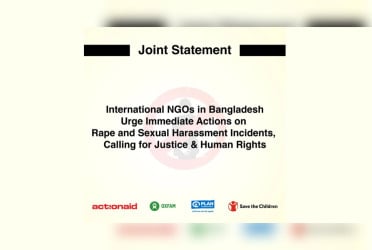

The situation in the country is far from ideal. Civil society think tank, CPD, in a press conference on Wednesday (January 29), criticized the economic policies of the Interim Government. CPD stated that the government has failed to take steps to ease the business environment, and the law and order situation is deteriorating. The Home Adviser himself has admitted that the police have shown no initiative. The prices of essential commodities are out of control, and various conspiracies are emerging everywhere. The way out of this crisis, according to CPD, is for the political leadership to take responsibility for running the country. Each person should be allowed to do their designated job. The responsibility of running the state lies with politicians. A vibrant national parliament will determine the future framework for various reforms in Bangladesh. The people are the true owners of the power in this country, and it is they who will decide which reforms will take place and which will not. If any attempt is made to forcefully impose anything on the people, the consequences will be clear, and the civil society is well aware of this. Hence, it is expected that civil society will have a self-realization before they fail again. Before BNP and other political parties go into protest demanding elections, the most urgent task is to have a formal declaration for a free, fair, and neutral election. Otherwise, under the pressure of protests, this interim government will inevitably collapse.

The writer is a playwright and columnist. She can be reached at [email protected]

Translated by ARK/Bd-Pratidin English