Intermittent fasting, popular among celebrities and leaders like British PM Rishi Sunak, is praised for its health benefits, including potential lifespan extension. However, while fasting may aid in body repair, dietitians warn it might not be the best for weight loss and caution against skipping meals without proper guidance.

Intermittent fasting is a type of time-restricted diet in which fasters leave a long gap between their last meal of one day and first of the next, compressing their meals into a shorter period during the day.

Typically, fasters try to leave a gap of 16 hours without food and eat during an eight-hour window.

Intermittent fasting is not the only type of time-restricted diet. Others like the 5:2 diet (in which dieters eat a normal amount of food for five days before two days of eating only 25% of their usual calorie intake) focus more on the amount of food consumed, rather than the time between meals.

"Time-restricted feeding is used as a weight loss tool, but it’s not my favourite approach," says Rachel Clarkson, founder of London-based consultancy The DNA Dietitian. "You reduce calories but you don’t learn the essential behaviour change around what you're putting into your body."

Clarkson says that without learning what a healthy diet looks like people gain weight again when they stop fasting. "If it means you are feeling starved and restricted then the next day you might over-eat.

So, intermittent fasting might not be the right approach for people seeking weight loss, but there might be other reasons to change your eating patterns. Fasting is linked to a process called autophagy, which is attracting a lot of interest for its potential health benefits.

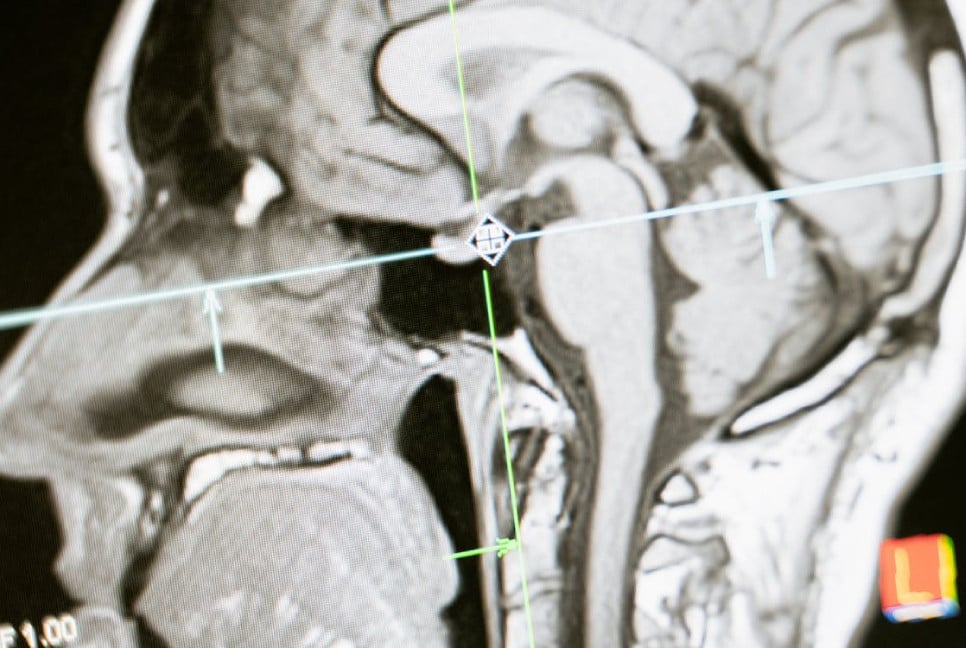

Autophagy is the process by which the body starts to recycle the structures inside its cells, including the nucleus, where DNA is stored, the mitochondria, which synthesise the chemical our cells use for energy, and lysosomes, which remove waste from our cells. In doing so, the cell can remove defunct structures, freeing up new raw materials from which new cellular structures can be built. Some of the new raw material might be used to make cell-protective proteins that further extend the lifespan of cells.

There is interest in whether autophagy can increase the lifespan of whole organisms, too – though so far this has only been replicated in animals, like 1mm-long nematode worms and mice, and not humans (inhibited autophagy has also been linked to early-onset ageing). Until there are longitudinal studies of human intermittent fasters, it is too soon to say that it will extend our lifespans.

But, other animal studies have linked autophagy to improvements in immune system memory. The fact that autophagy is essential to maintain cell health has also generated interest in its role in cancer suppression. There might be more reasons than increasing lifespan to take interest in autophagy.

For most of us, autophagy occurs in our sleep, but it is also brought on by exercise and starvation. Could controlled fasting help to trigger it?

Unlike calorie-restricted diets, which are also linked to longer life, the goal of intermittent fasting is to extend the time between the last meal of one day and the first meal of the next. While an intermittent faster could eat the same number of calories, most people tend to eat a little less. This approach may help promote autophagy, but to understand its effects, we need to look at what happens after eating.

Clarkson explains that after stopping eating at 7pm, you remain in the "fed state" until about 10pm, as your body continues digesting nutrients, especially glucose from carbohydrates. In the fed state, the body uses glucose for energy. After the glucose is depleted, it enters a catabolic state, breaking down glycogen into glucose, and eventually shifts to burning ketones for energy in a process called ketosis, triggering autophagy.

The timing of this shift depends on factors like diet and activity level. People with high-carb diets may stay in the catabolic state longer, while those on low-carb or keto diets may transition quickly. Clarkson advises against using intermittent fasting solely for weight loss and recommends focusing on its health benefits.

A recent, yet unpublished study of 20,000 US adults over 17 years suggests that fasting for an eight-hour window may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease compared to eating within 12-16 hours.

How to fast

Clarkson explains that fasting requires controlling hunger, which is triggered by the hormone ghrelin. Ghrelin activates hunger by releasing two additional hormones, but other hormones, like leptin, suppress hunger by signaling fat storage to be used as energy. Ghrelin, the short-term hunger hormone, is produced when the stomach is empty, but it can be reduced by drinking water. Leptin, which works over the long term, helps to regulate hunger.

Hunger hormones are influenced by various factors, including genetics and stomach signals. Clarkson advises staying hydrated to curb early hunger, which eases over time. Ketosis, the process where the body switches to burning fat for energy, typically starts 12-24 hours after eating. However, snacking or sugary drinks can delay ketosis. Clarkson recommends eating earlier in the evening and avoiding snacks for better results.

While intermittent fasting can help with body repairs and recovery, especially as autophagy declines with age, it may not be the best strategy for weight loss. A balanced diet remains essential.

Source: BBC

Bd-pratidin English/ Afia