On the grounds of a gas-fired power plant on Canada’s east coast, an emerging company is pumping mineral-rich slurry into the ocean, hoping to combat climate change. Whether this is pollution or a breakthrough depends on perspective.

Planetary Technologies, a Nova Scotia-based firm, is betting that adding magnesium oxide to seawater will enhance the ocean’s natural carbon absorption. With a $1 million grant from Elon Musk’s foundation and a shot at a $50 million prize, the company is among a growing number of startups exploring ocean-based carbon removal.

From sinking rocks to cultivating seaweed, nearly 50 field trials have taken place in the past four years, with industry funding soaring into the hundreds of millions. But critics warn that scaling up these methods without sufficient oversight could have unintended consequences.

“It’s like the Wild West,” said Adina Paytan, an earth and ocean sciences professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Everyone is jumping in, eager to contribute.”

Planetary, like many startups, finances its operations by selling carbon credits—certificates representing a metric ton of carbon dioxide removed. These credits, while controversial and largely unregulated, can fetch hundreds of dollars each. Last year, over 340,000 marine carbon credits were sold, a significant rise from just 2,000 four years earlier, though still far below the scale required to make a global impact.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated that cutting emissions alone won’t be enough to curb global warming. Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is critical, and the ocean—a vast natural regulator of the planet’s climate—is an attractive target.

Land-based carbon removal methods, such as direct air capture and reforestation, are constrained by space and community concerns. In contrast, the ocean appears nearly limitless. However, uncertainty remains about the long-term impact of large-scale interventions.

"Can the ocean’s vast surface area help mitigate climate change?" asked Adam Subhas, who leads a carbon removal project at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

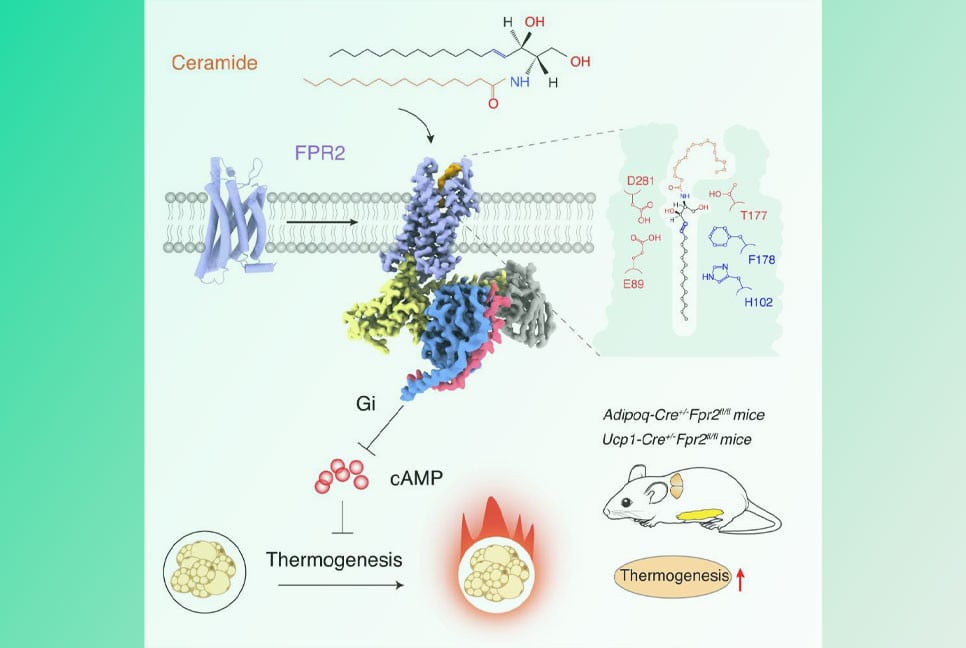

Planetary’s approach dissolves magnesium oxide into seawater, converting carbon dioxide into stable molecules that remain locked away for millennia. Similar efforts involve limestone, olivine, or even the cultivation of seaweed and algae to absorb carbon naturally.

Other companies are experimenting with deep-sea storage, submerging organic materials like wood chips or seaweed to keep carbon out of the atmosphere. New Zealand-based Gigablue is adding nutrients to stimulate phytoplankton growth, while Carboniferous is seeking approval to deposit sugarcane pulp in the Gulf of Mexico.

Planetary’s chief ocean scientist, Will Burt, acknowledges the uncertainties. "This may seem like a ‘scary science experiment,’ but early tests suggest minimal risks to marine life." Magnesium oxide, he notes, is already used in water treatment facilities to neutralize acidity.

Halifax Harbour is just one of Planetary’s test sites. Trials are also underway at a wastewater facility in Virginia, with Vancouver next on the list.

Despite industry optimism, not all coastal communities are welcoming these efforts.

In North Carolina, a project to spread olivine near the town of Duck was scaled back after regulatory concerns over marine ecosystems. Similarly, protests in Cornwall, England, forced Planetary to halt a planned magnesium hydroxide release.

Even scientists remain divided. While some methods have been studied for decades, large-scale implementation introduces unpredictable variables. Tracking how added materials behave in the ocean—whether they sink, disperse, or alter chemistry—is challenging.

The biggest question is longevity. Organic materials like seaweed or wood chips could eventually decompose, re-releasing carbon. Some estimates predict millennia of storage, while others suggest only decades.

Scaling up to the billions of tons needed annually also requires vast resources, energy, and funding.

But with global temperatures reaching record highs and carbon emissions still climbing, many believe inaction is the greater risk.

“The alternative to trying,” said David Ho, an oceanography professor at the University of Hawaii, “is allowing climate change to continue unchecked.”

Source: UNB

Bd-pratidin English/ Jisan