The ongoing power cut situation in Bangladesh and the economic effects of this reason have been highlighted in a report published on Wednesday (August 24) by the Financial Times, a British daily newspaper.

The report, titled, Bangladesh: global economic crisis hammers south Asia’s export powerhouse by Benjamin Parkin in Dhaka and John Reed in New Delhi.

It reads: Mohammad Sharif Sarker’s factory is in many ways a model. Spread over three spacious floors in Ashulia, a suburb of Bangladesh’s capital Dhaka, hundreds of young women and men sit in orderly assembly lines, sewing machines before them, ready to stitch trendy flat-brim caps for export.

There’s only one problem: Sarker and his workers are sitting in the dark, their machines idle. Ashulia is currently in the middle of one of the daily mandatory power cuts that the government introduced in July, as Bangladesh grapples with a severe energy crunch. And with a recent government-mandated 50 per cent increase in fuel prices, Sarker has opted to keep the power off while his workers take a lunch break, rather than fire up an expensive diesel-powered generator.

“The sector will be unsettled if the price of everything keeps going up,” Sarker says. “It is the workers who will ultimately carry the burden.”

Factories like his have helped propel Bangladesh, previously one of the world’s poorest countries, to become the third-largest garment exporter after China and Vietnam according to World Trade Organization data — notching up significant gains in income, education and health along the way. In South Asia, a region of almost 2bn people across India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, Bangladesh stood out for its development and success in fostering a globally competitive goods export sector.

But now, along with most of its south Asian neighbours, the country of 160mn people is being rocked by soaring prices of energy and food following the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These have led to energy shortages and rising import bills that are, in some cases, straining their ability to keep up with debt payments.

The regional economic crisis in south Asia has been swingeing in its casualties, claiming countries whose governments pursued reckless spending policies, such as Sri Lanka, alongside model development economies. It now threatens to reverse hard-won, generational gains made in the world’s most populous emerging market region, which sits at the geopolitical junction where Indian and Chinese interests meet.

“The crisis is punishing countries with an array of different economic performances and models,” says Mark Malloch Brown, a former UN and World Bank official who now heads the George Soros-backed Open Society Foundations. “Bangladesh, a very internationally oriented economy known for its garment sector, is getting killed by economic conditions elsewhere in the world.”

Along with most of its south Asian neighbours, the country of 160mn people is being rocked by soaring prices of energy and food following the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These have led to energy shortages and rising import bills that are, in some cases, straining their ability to keep up with debt payments.

“Bangladesh, a very internationally oriented economy known for its garment sector, is getting killed by economic conditions elsewhere in the world,” says Mark Malloch Brown, a former UN and World Bank official who now heads the George Soros-backed Open Society Foundations.

Bangladesh had until recently been better insulated from recent economic shocks, in part because of its successful export sector. But Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s government in July approached the IMF for a loan to try and shore up its foreign currency reserves and help the low-lying country build resilience against climate change. Bangladesh is seeking about $4.5bn from the fund, and as much as $4bn more from other lenders, including the World Bank and Asian Development Bank.

In addition to raising fuel prices, which triggered protests, Bangladesh’s government has cut school and office hours to conserve energy and introduced import restrictions on luxury goods to protect its foreign reserves.

Bangladesh, for example, was forced to shut its diesel power plants in July due to import shortages. Some of these countries also owe money to China for projects pursued under Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, adding a layer of geopolitical risk to any coming debt workouts for regional economies in peril.

The IMF says that with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 39 per cent — lower than its neighbours — Bangladesh is “not in a crisis”, but warns the country is vulnerable to the “huge uncertainty surrounding global economic developments”.

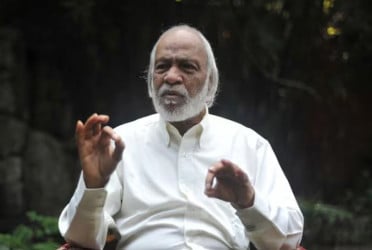

Rashed al Mahmud Titumir, an economics professor at Dhaka University, argues that the international community should step in to protect the hard-won gains of Bangladeshi workers. “You see the working class has a kind of resilience,” he says. “The west and the [lending] institutions should look at that . . . it should not be allowed to free fall.”

Unlike Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan “have never really been forced to try to improve economic policymaking”, he says.

Bd-pratidin English/Golam Rosul