Scientists have found that a huge meteorite discovered in 2014 triggered a tsunami bigger than any recorded in human history and caused the oceans to boil.

This space rock was 200 times bigger than the asteroid that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs and struck Earth approximately three billion years ago, during the planet's early formation.

With sledgehammers in hand, scientists trekked to the impact site in South Africa to chip away at the rock and learn more about the crash.

The team also uncovered evidence that these massive asteroid impacts didn't just lead to destruction; they actually helped early life to flourish.

Prof. Nadja Drabon from Harvard University explained that after Earth formed, many debris pieces were still colliding with the planet. She discovered that life was surprisingly resilient and thrived following these significant impacts.

The S2 meteorite was far larger than the asteroid that caused the dinosaurs' extinction 66 million years ago. While that asteroid was about 10 kilometers wide, the S2 meteorite measured between 40 and 60 kilometers across, making it 50 to 200 times heavier.

This meteorite struck Earth when it was very young, mostly covered in water with only a few continents visible. At that time, life was simple, primarily consisting of single-celled microorganisms.

The impact site located in the Eastern Barberton Greenbelt is one of the oldest on Earth with evidence of a meteorite collision. Prof. Drabon made three trips there with her team, driving as far as they could into the remote mountains before hiking the rest of the way. They were accompanied by rangers armed for protection against wildlife and poachers in the region.

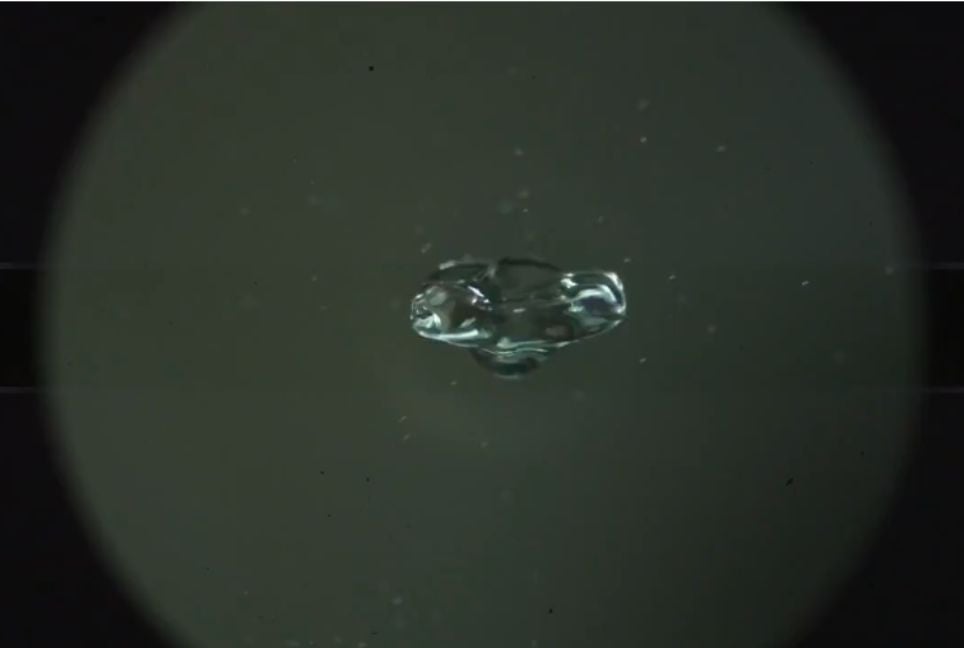

They sought tiny rock fragments known as spherules, created by the impact. Using sledgehammers, they collected hundreds of kilograms of rock for analysis in laboratories. Prof. Drabon humorously mentioned that she often gets stopped by security but is eventually allowed through after explaining the scientific significance of her samples.

The team reconstructed how the S2 meteorite struck Earth, creating a massive 500-kilometer-wide crater and ejecting rocks into the atmosphere, which formed a cloud of debris. Prof. Drabon compared it to a rain cloud, except molten rock rained down instead of water. This event likely caused a colossal tsunami that flooded coastlines, far larger than the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

The energy from the impact generated intense heat, boiling the oceans and causing vast amounts of water to evaporate, while air temperatures may have soared by up to 100 degrees Celsius. The sky would have turned dark due to dust and debris, blocking sunlight and eliminating simple life forms that relied on photosynthesis.

While earlier studies on significant meteorite impacts suggested similar outcomes, Prof. Drabon and her team were surprised to find that the disturbances actually released nutrients like phosphorus and iron, which supported simple organisms. She likened this to brushing your teeth: "It kills 99.9% of bacteria, but by the evening, they're all back," highlighting how quickly life rebounded after the impacts.

This new research suggests that these major impacts acted as giant fertilizers, distributing essential nutrients for life across the planet. The resulting tsunami would have also brought nutrient-rich water to the surface, giving early microbes additional energy.

These findings support the theory that early life on Earth was positively impacted by the large meteorite strikes during its formative years, allowing life to thrive afterward.

The study's results were published in the scientific journal PNAS.

Source: BBC

Bd-pratidin English/Afia