The concept of sisu has no direct translation, encompassing extreme perseverance and dignity in the face of adversity. But can it be learnt?

‘Sisu’ in Finnish means strength, perseverance in a task that for some may seem crazy to undertake, almost hopeless. Sinior finish citizens experienced the bombings of the Winter War (1939-1940) when Finland was attacked by the much superior Soviet army but managed to mount a resistance to remain independent. The New York Times ran an article in 1940 with the headline “Sisu: A Word that Explains Finland”.

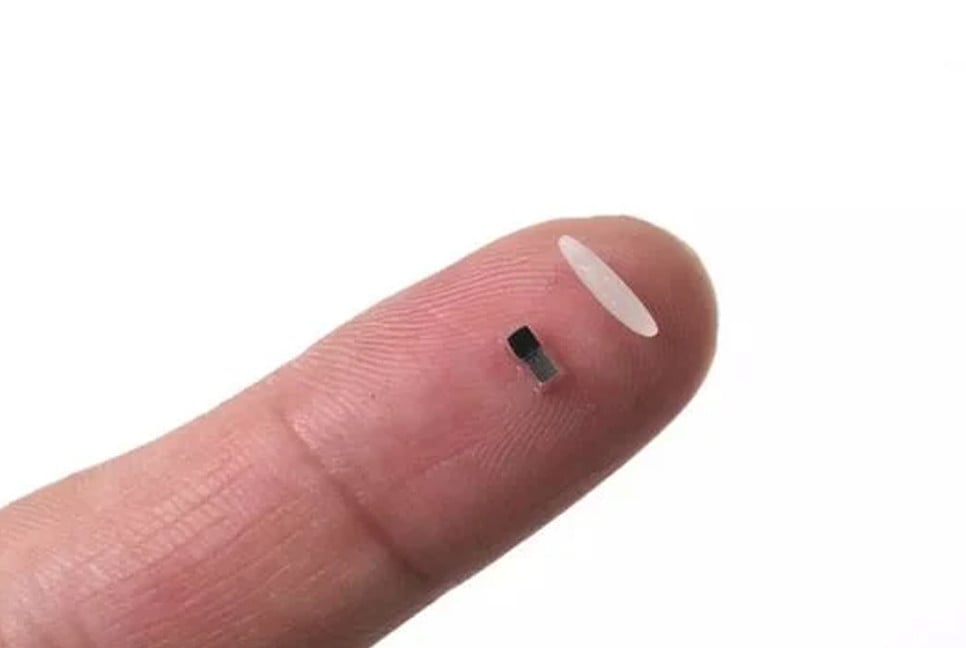

The word originates from ‘sisus’, which literally means ‘guts’ or ‘the intestines’ in Finnish

So, what is this almost mythical quality that appears to be so Finnish? “It is a special thing that is reserved for especially challenging moments. When we feel that we came to the end point of our preconceived capacities. You could say that sisu is energy, determination in the face of adversities that are more demanding than usual,” says Emilia Lahti, a researcher of sisu from Aalto University in Helsinki.

Lahti’s route to a fascination with sisu is through survival and success after a physically and psychologically abusive relationship, and she has also become a social campaigner and promoter of sisu. “We all have these moments when we all need to reach beyond what we think we are capable of. At the end of physical, emotional and psychological endurance. And then we have some kind of force that allows us to continue even when we thought we couldn’t,” says Lahti. For Finns, that ‘second wind’ of inner strength is sisu.

What’s in a word?

The history of the concept may help us understand its continuing resonance in Finnish culture today. The word originates from ‘sisus’, which literally means ‘guts’ or ‘the intestines’ in Finnish. In 1745, Daniel Juslenius, a Finnish bishop, defined ‘sisucunda’ in his dictionary as the location in the human body where strong emotions come from.

“With Lutheran philosophy this word came to denote more of a bad quality, that you are somebody really bad at taking orders, a misfit,” says Lahti. But the idea of sisu came to be embraced by Finnish intellectuals as a particularly Finnish quality during the period the new nation was built. Finland became independent from Russia in 1917, and sisu can be seen as a ‘social glue’ that helped define the nation.

“In the 20s they needed to find some characterisation for Finns as an independent nation. So sisu was a very good positive thing. It gave us a feeling that there is something positive about us. It gave us the reason why we have survived as a nation in the cold. It was a young nation looking for those positive sorts of images of itself. All this strengthened the idea that there was something special in the Finns,” Rauno Lahtinen, cultural historian from Turku University points out.

Finnish history during the last 100 years has reinforced the notion of sisu as a particularly Finnish trait. Following Winter War, Finland honourably paid in full its reparations to the Soviet Union, despite the great hardship this imposed on the nation, so avoiding further threats to its independence. Sisu captured the sentiment of the country’s honourable survival.

The word is also frequently used to explain Finland’s sporting achievements and feats of physical endurance. Veikka Gustafsson became a national symbol of sisu in the 1990s, when he became the first Finn to climb Mount Everest in 1993. By 2009 he had climbed all 14 of the world’s 8,000m peaks (eight-thousanders, as they are called) without supplementary oxygen. This made him the ninth climber in the world to have achieved this. He also climbed peaks in Antarctica, naming one of them ‘Mount Sisu’.

Gustaffson not only named a mountain after Sisu; his five-year-old son is also called Sisu, and for a while (not any more) he became the face of a popular Finnish sweet called “sisu pastils”.

Having become the embodiment of sisu, who does Gustaffson admire as having sisu? “If I think of the Sherpa people in Nepal, they have lots and lots of sisu. And I think the Balti people who were helping us in the expeditions in Pakistan. They also have lots and lots of sisu,” he says.

For all the sweetness of sisu pastils, sisu has its downsides. Even Gustafsson admits that Finnish sisu also denotes an element of stubbornness, “I do my own thing. If you have sisu, you don’t just endure adversity but you endure what Emilia Lahti calls ‘silent relentlessness’,” he says.

Sisu can also make it difficult to admit weakness. “It’s hard to ask for help. You risk losing face if you admit weakness. That’s a challenge in a culture that holds sisu in high reverence’, Emilia Lahti tells others. If you persevere for too long, results could be damaging. “You might end with burnout if you try too hard.” You can also cause harm to others with too much sisu, she warns. “It’s almost too easy to impose this merciless attitude on other people as well. And it’s very hard to be around people like that.”

Young people are not even proud of being Finnish or of having sisu, they often think things are better abroad – Aino Niemi

She stresses the importance of combining sisu with compassion both to yourself and to others. In the meantime, the role of sisu as a social glue in Finland seems to be diminishing. Its appeal to younger generations is falling.

Aino Niemi, a 23-year old Finn, agrees that sisu has become something of a platitude. “For example, when Finland wins the ice hockey World Championship then we are proud that we have sisu,” she says. “But most of the time sisu is not important, young people are not even proud of being Finnish or of having sisu, they often think things are better abroad.”

Nordic export

Lahti is keen to stress that many other cultures have comparable concepts: the Japanese ‘ganbaru’, which means going tenaciously through rough times. There is also the ‘stiff upper lip’ that the British have been proud of for centuries.

But it is sisu, in particular, that seems to have captured the imagination abroad. This may be due, in part, to the idea that Nordic countries hold the secret of personal fulfilment.

Before sisu, the world came to admire another Nordic export, the Danish (and Norwegian) idea of ‘hygge’, which means comfortable cosiness and conviviality, and Swedish ‘lagom’, which is all about balance and moderation and simplicity. Another Finnish pastime is threatening to edge sisu out of the limelight. It’s ‘kalsarikännit’, which means ‘getting drunk in your underwear at home’. A new emoji has already appeared for this concept.

Many want to believe that these Finnish ways of doing things could make us happy and independent, as some Finns are. In reality it’s the investment needed in education and social provision that makes people feel more fulfilled in their lives.

Sisu clearly isn’t the only explanation for Finnish success, but Gustafsson is adamant that the country would not be the same without it. “If it had not been for sisu, I would have been speaking Russian to you,” he tells me – a reminder of the Soviet attack in 1939 when Finland managed to preserve its independence.

Wherever you live, that same spirit of resilience is still worth remembering today, says Gustafsson: “The biggest obstacles are between our ears, what we tell ourselves.”

Source: BBC

Bd-pratidin English/Lutful Hoque