Have you ever been convinced that you remember being a baby? A moment in a crib, or the taste of a first birthday cake?

Chances are, those memories aren’t real. Decades of research suggest that most people cannot recall personal experiences from the first few years of life.

However, even though we can’t remember being a baby, a new study has found new evidence that babies do take in the world around them and may also begin forming memories far earlier than once thought.

How did the study work and what did it find?

A study by Yale and Columbia universities, published in Science, reveals that babies as young as 12 months can form memories through the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory storage in adults.

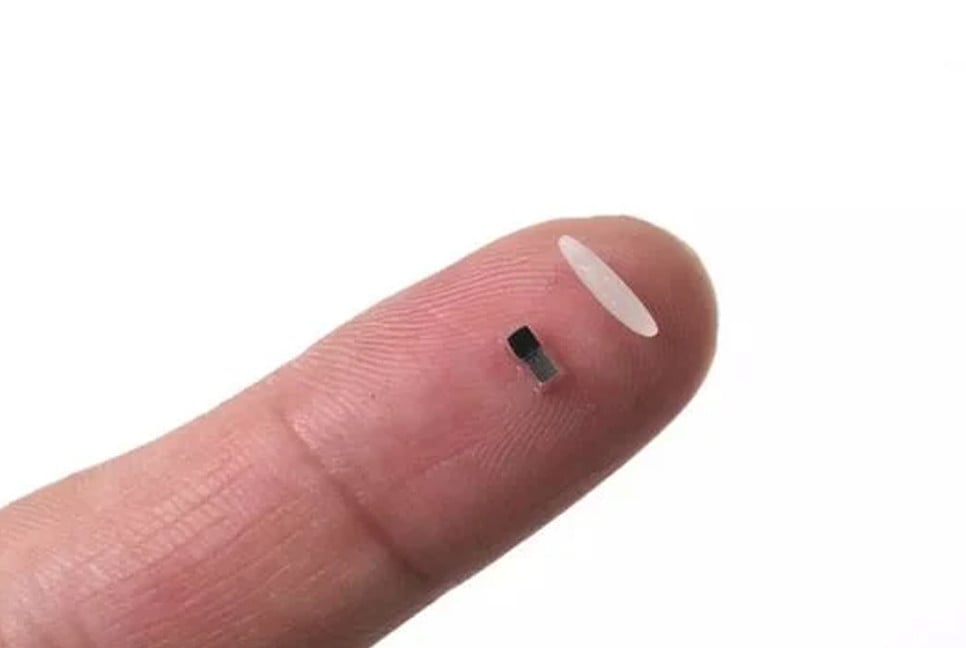

Using a specially adapted brain scan, researchers observed 26 infants (aged 4-25 months) as they looked at images. They found that babies whose hippocampus was more active the first time they saw an image tended to look longer at the same image when it reappeared, indicating memory recognition.

This is the first direct observation of memory formation in awake babies, as previous studies relied on indirect methods. The study suggests that babies' brains can form memories, though the duration of these memories remains unclear.

What does this tell us about early life memories?

The findings suggest that episodic memory – the kind of memory that helps us remember specific events and the context in which they took place – begins to develop earlier than scientists previously believed.

Until recently, it was widely believed that this type of memory didn’t begin to form until well after a baby’s first birthday, typically around 18 to 24 months. Although the findings from the Science study were strongest in infants older than 12 months, the results were observed in much younger babies as well.

So, at what age do we start making memories?

It is now understood that babies begin forming limited types of memory when they are as young as two or three months. These include implicit memories (such as motor skills) and statistical learning, which helps infants detect patterns in language, faces and routines.

However, episodic memory, which allows us to recall specific events as well as where and when they occurred, takes longer to develop and requires the maturation of the hippocampus.

According to Cristina Maria Alberini, professor of neural science at New York University, the period in infancy when the hippocampus is developing its ability to form and store memories may be “critical”. This window could be important not only for memory but also has “great implications for mental health and memory or cognitive disorders”, she added.

Memories formed in early childhood do not typically last very long, it is believed, which might explain why we can’t remember them later in life. In an ongoing study at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Germany, 20-month-old toddlers were able to remember which toy was in which room for up to six months, while younger children retained the memory for only about one month.

Why can’t we remember anything from infancy?

"Infantile amnesia," the inability to recall memories before age three, has long been attributed to immature brains. However, recent research shows babies can form memories.

One explanation is rapid neurogenesis, where new neuron growth disrupts old memories. Another theory suggests episodic memory requires language and a sense of self, which develop later.

Some researchers believe forgetting early memories helps the brain focus on learning general knowledge rather than irrelevant details.

Source: Al Jazeera