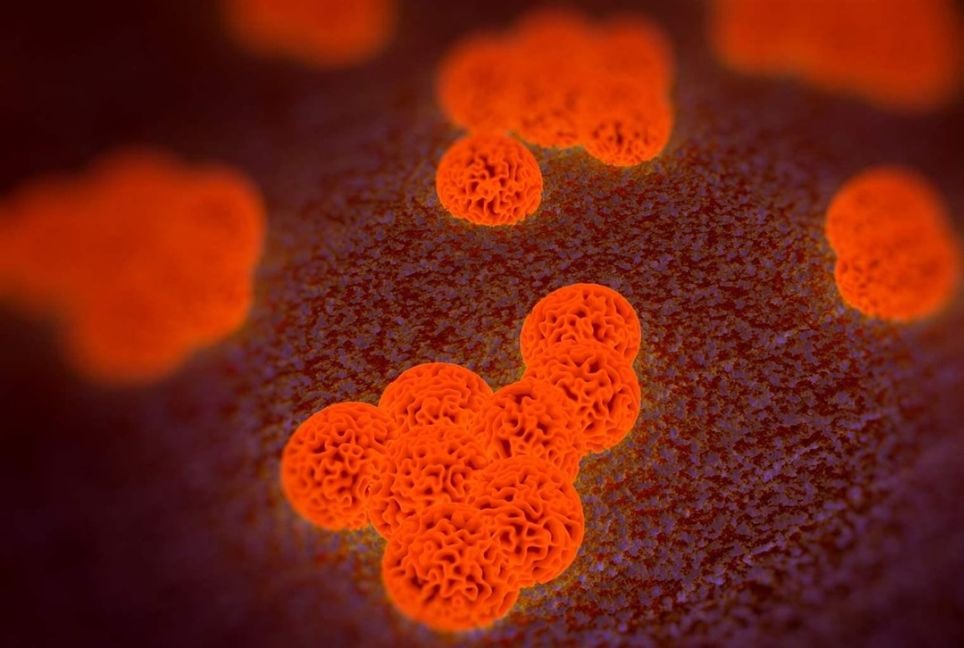

A study from Boston University (BU) suggests that microplastics—tiny plastic particles prevalent in oceans, mountains, and even human bodies—might contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Researchers discovered that bacteria exposed to microplastics became resistant to several commonly used antibiotics.

Study insights

The BU team examined how the common bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli) behaved when in contact with microplastics within a controlled setting. They observed that microplastics served as surfaces for bacterial attachment and colonization, forming biofilms—a sticky protective layer that shields bacteria from external threats. These biofilms were significantly thicker and stronger on microplastics compared to other surfaces like glass.

Lead researcher Neila Gross reported that even when antibiotics were introduced, the biofilm barrier prevented the drugs from penetrating, allowing bacteria to thrive. After repeating the experiments with different antibiotics and plastic types, the results consistently demonstrated a high rate of resistance.

Risks and concerns

The findings, published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, are particularly concerning for impoverished areas where plastic waste accumulates and bacterial infections spread rapidly.

Muhammad Zaman, a BU professor of biomedical engineering, emphasized that disadvantaged communities face a heightened risk and stressed the need for deeper investigation into how microplastics and bacteria interact.

Why it matters

Antimicrobial resistance already causes approximately 4.95 million deaths per year. While factors like improper antibiotic use play a role, the immediate environment where bacteria grow also significantly influences resistance. Microplastics appear to enhance bacterial defenses, making it harder to treat infections.

The research team plans to study whether these lab findings are mirrored in real-world conditions, highlighting the urgent need to address plastic pollution's impact on public health.

Courtesy: ANI

Bd-pratidin English/FNC