Scientists say they have recovered the oldest known Homo sapiens DNA from human remains found in Europe, and the information is helping to reveal our species’ shared history with Neanderthals.

The ancient genomes sequenced from 13 bone fragments unearthed in a cave beneath a medieval castle in Ranis, Germany, belonged to six individuals, including a mother, daughter and distant cousins who lived in the region around 45,000 years ago, according to the study that published Thursday in the journal Nature, reports CNN.

The genomes carried evidence of Neanderthal ancestry. Researchers determined that the ancestors of those early humans who lived in Ranis and the surrounding area likely encountered and made babies with Neanderthals about 80 generations earlier, or 1,500 years earlier, although that interaction did not necessarily happen in the same place.

Scientists have known since the first Neanderthal genome was sequenced in 2010 that early humans interbred with Neanderthals, a bombshell revelation that bequeathed a genetic legacy still traceable in humans today.

A broader study on Neanderthal ancestry, published Thursday in the journal Science, that analyzed information from the genomes of 59 ancient humans and those of 275 living humans corroborated the more precise timeline, finding that the majority of Neanderthal ancestry in modern humans can be attributed to a “single, shared extended period of gene flow.”

The research also showed how certain genetic variants inherited from our Neanderthal ancestors, which make up between 1% and 3% of our genomes today, varied over time.

Some, such as those related to the immune system, were beneficial to humans as they lived through the last ice age, when temperatures were much cooler, and they continue to confer benefits today.

How Neanderthal ancestry has shaped human genes

The research in Science found that genetic variants inherited from our Neanderthal ancestors are unevenly distributed across the human genome.

Some regions, which the scientists call “archaic deserts,” are devoid of Neanderthal genes. These deserts likely developed quickly after the two groups interbred, within 100 generations, perhaps because they resulted in birth defects or diseases that would have affected the survival chances of the offspring.

“It suggests that hybrid individuals who had Neanderthal DNA in these regions were substantially less fit, likely to due to severe disease, lethality, or infertility,” Capra said via email.

In particular, the X chromosome was a desert. Capra said the effects of Neanderthal variants that cause disease could be greater on the X chromosome, perhaps because it is present in two copies in females, but only present in one copy in males.

“The X chromosome also has many genes that are linked to male fertility when modified, so it has been proposed that some of this effect could have come from introgression leading to male hybrid sterility,” he said.

The new timeline allows scientists to understand better when humans left Africa and migrated around the world. It suggested that the main wave of migration out of Africa was essentially done by 43,500 years ago because most humans outside Africa today have Neanderthal ancestry originating from this period, the Science study suggested.

However, there is still much scientists don’t know. It’s not clear why people in East Asia today have more Neanderthal ancestry than Europeans, or why Neanderthal genomes from this period show little evidence of Homo sapiens DNA.

Lost branch of the human family tree

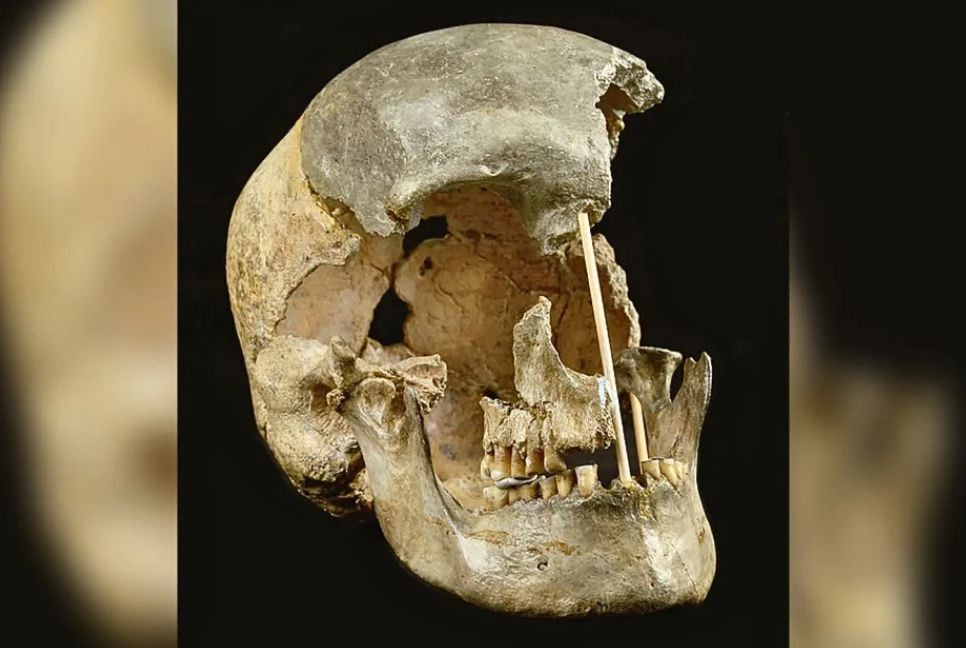

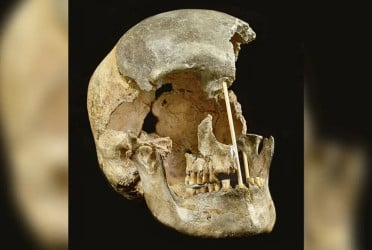

The individuals who called the cave in Ranis home were among the first Homo sapiens to live in Europe.

These early Europeans numbered a few hundred and included a woman who lived 230 kilometers (143 miles) away in Zlatý kůň in the Czech Republic. DNA from her skull was sequenced in a previous study, and researchers involved in the Nature study were able to connect her to the Ranis individuals.

These individuals had dark skin, dark hair and brown eyes, according to the study, perhaps reflecting their relatively recent arrival from Africa. Scientists are continuing to study remains from the site to piece together their diet and how they lived.

The family group was part of a pioneer population that eventually died out, leaving no trace of ancestry in people alive today. Other lineages of ancient humans also went extinct around 40,000 years ago and disappeared just like the Neanderthals ultimately did, said Johannes Krause, director at the department of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. These extinctions may suggest that Homo sapiens did not play a role in the demise of Homo neanderthalensis.

Bd-pratidin English/Fariha Nowshin Chinika