A newly discovered set of insect fossils, described as “extremely rare” by researchers, is shedding light on New Zealand’s ancient ecosystems. The fossils, which belong to adult whitefly insects, were uncovered in Miocene-aged sediments at the Hindon Maar crater lake near Dunedin. The findings were published in the journal Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments, University of Otago stated on Tuesday.

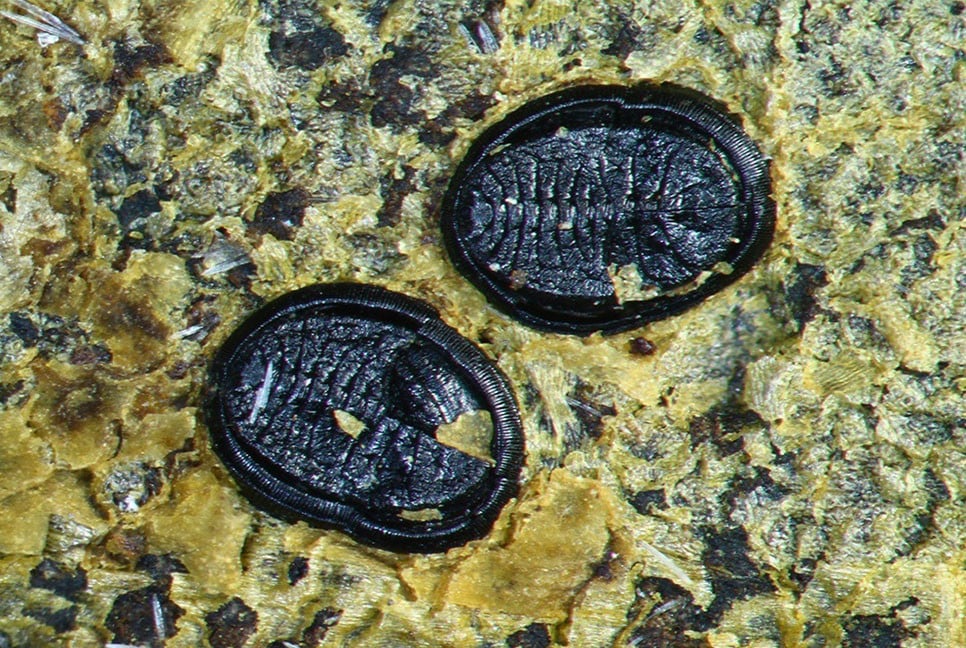

The whitefly fossils, measuring just 1.5mm by 1.25mm, are exceptionally well-preserved, remaining in the position in which the insects lived and died—attached to the underside of a fossilized leaf. While modern-day whiteflies are small, around 3mm in size, these ancient insects share similarities in shape and color but stand out for having all body segments distinctly defined by deep sutures, a feature not found in their modern counterparts.

Dr. Uwe Kaulfuss, a co-author of the study and researcher at the University of Göttingen in Germany, discovered the tiny fossils during an excavation earlier this year. He explained that while fossils of adult whitefly insects are not uncommon, “it takes extraordinary circumstances for the puparia—the protective shell the insect emerges from—to become fossilised.” According to Dr. Kaulfuss, the preservation of these fossils likely occurred when a leaf, carrying the insect puparia, was detached from a tree, blown into the small lake, and sank to the lake floor, where it was rapidly covered by sediment. “It must have happened in rapid succession as the tiny insect fossils are exquisitely preserved,” he said.

This discovery is significant for understanding ancient ecosystems, as it is the first evidence of whiteflies in New Zealand. "The new genus and species described in our study reveals for the first time that whitefly insects were an ecological component in ancient forests on the South Island,” Dr. Kaulfuss noted.

Emeritus Professor Daphne Lee from the University of Otago, a co-author of the study, described the discovery as "incredible" due to the fact that the fossils are still in their “life position” on the leaf, a preservation feat she called “extremely rare.” She added, “These little fossils are the first of their kind to be found in New Zealand and only the third example of such fossil puparia known globally.”

Professor Lee also emphasized how the discovery fits into a broader picture of New Zealand’s pre-Ice Age insect fauna. “Until about 20 years ago, the total number of insects in the country older than the Ice Ages was seven, and now we have 750,” she said. “New discoveries such as these from fossil sites in Otago mean we’ve gone from knowing almost nothing about the role played by insects to a new appreciation of their importance in understanding New Zealand’s past biodiversity and the history of our forest ecosystems.”

Lee further highlighted the significance of insect fossils in understanding ancient forest life, noting that “most animals in forests are insects,” and that New Zealand is home to around 14,000 insect species, 90% of which are unique to the country. “Discovery of these minute fossils tells us this group of insects has been in Aotearoa New Zealand for at least 15 million years,” she said, providing a valuable "well-dated calibration point for molecular phylogenetic studies."

Other recent fossil discoveries in Otago include the first-ever fossils of danceflies, craneflies, phantom midges, and marsh beetles from New Zealand. These discoveries demonstrate the global significance of Otago as a key site for paleontological research, with collaborations involving scientists from Germany, France, Spain, Poland, and the United States.

Bd-pratidin English/ Jisan Al Jubair