In the turbulent political landscape of Bangladesh, the term "One-Eleven" evokes memories of a dark era marked by the 2007 military-backed caretaker government. In recent times, the echoes of that period are resurfacing with alarming regularity, prompting widespread concern among political parties and civil society. As the nation stands at a critical juncture following the August 5 revolution, political unity against a repeat of One-Eleven has grown louder and more resolute.

Political leaders from across the spectrum have warned of a covert plot to orchestrate another One-Eleven-style intervention. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the National Citizen Party (NCP), among others, have made it clear that any such attempt will face fierce resistance.

BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir has stated unequivocally, "If anyone dreams of another One-Eleven, they are mistaken." Echoing his sentiments, BNP Standing Committee members Salahuddin Ahmed and Mirza Abbas have reiterated that any force attempting to usher in another version of that regime will be resisted. NCP leaders, including Hasnat Abdullah and Convener Nahid Islam, have also voiced strong opposition and urged public vigilance against such conspiracies.

Behind the scenes, however, there are allegations of a coordinated effort by certain civil society groups and media organizations to lay the groundwork for such a scenario. At the center of these claims are two major English-language newspapers: Prothom Alo and The Daily Star. Accused of being aligned with foreign interests—most notably Indian strategic agendas—these outlets are alleged to be working to destabilize the country's private sector under the guise of anti-corruption.

Critics argue that this group, long seen as aligned with the Awami League, played a key role in enabling the original One-Eleven and is now attempting to reprise that role by spreading misinformation and targeting influential business leaders. The goal, they claim, is to fracture the economic backbone of Bangladesh: the private sector.

During the One-Eleven regime in 2007, the military-backed caretaker government launched an aggressive campaign that resulted in widespread harassment of both politicians and industrialists. Official statistics show that 762 business leaders were targeted, with fabricated corruption charges filed against them. Reports suggest that over BDT 4,725 crore (approx. USD 550 million) was illegally extracted from entrepreneurs under threat of prosecution, with the media playing a key role in orchestrating these campaigns.

Prothom Alo and The Daily Star published a flurry of sensational articles against business owners and political figures alike, often without verification. These stories were rapidly picked up by the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), which used them to justify raids, arrests, and the seizure of assets. The impact was devastating: social reputations were destroyed, businesses were crippled, and investor confidence plummeted.

This campaign of intimidation and misinformation is widely believed to have been part of a broader depoliticization agenda aimed at aligning Bangladesh more closely with Indian strategic interests. The Awami League, which came to power following the One-Eleven regime, is seen by critics as having continued many of its tactics, thus becoming an "extended version" of One-Eleven.

Notably, BNP Chairperson Begum Khaleda Zia was targeted with a controversial corruption case during that time—one that was aggressively pursued by the subsequent Awami League government, leading to her conviction and long-term imprisonment. Similarly, Tarique Rahman, BNP's acting chairman, was subjected to numerous cases seen by many as politically motivated.

The economic ramifications of the One-Eleven period still linger. The Supreme Court of Bangladesh later declared the illegal collection of fines from businessmen as unconstitutional and ordered the return of these funds. Yet, the directive remains largely unenforced. Critics argue that the government’s failure to act on the court's decision reflects a deeper continuity between the One-Eleven regime and subsequent administrations.

Today, fresh warnings are being issued against a resurgence of the same playbook. Over the past several months, numerous business leaders have reportedly faced undue harassment. Bank accounts have been frozen, assets seized, and accusations of foreign money laundering launched without substantiated evidence. Once again, Prothom Alo and The Daily Star stand accused of being at the center of these developments, publishing unverified reports that are then used to justify state action.

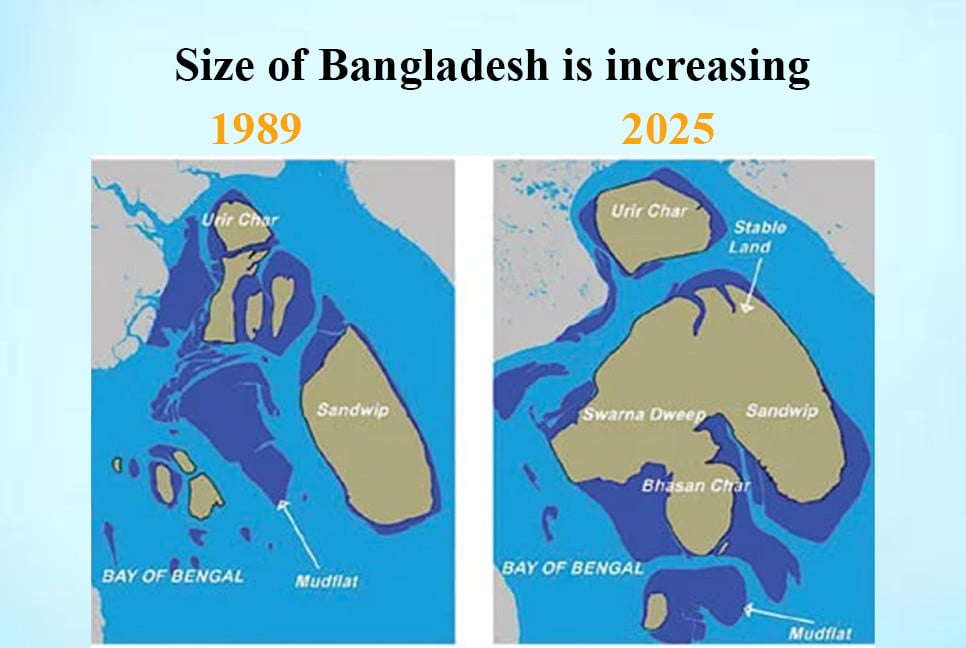

The implications are profound. Bangladesh’s economy has long been powered by a vibrant private sector that includes manufacturing, export-oriented industries, and a growing tech and service sector. Disrupting this ecosystem at a time when global economic headwinds are already straining growth could prove disastrous.

The parallels between then and now are difficult to ignore. Just as in 2007, today’s alleged campaign appears timed with heightened political tension and uncertainty. After the August 5 revolution, which led to significant political restructuring, several industrial facilities were mysteriously set on fire. Looting incidents in key economic zones have only added to business community fears. The concern is that these acts may not be coincidental but part of a broader strategy to sow chaos and justify extraordinary political measures.

While Prothom Alo and The Daily Star may now show restraint in criticizing political actors, critics argue that their focus has merely shifted to the private sector. Harassment campaigns against high-profile business conglomerates, often based on flimsy or nonexistent evidence, are being described as a "new formula" for implementing the One-Eleven agenda.

Political analysts suggest that this new strategy may serve a dual purpose: erode public trust in the private sector and create a pretext for the return of authoritarian governance under the guise of anti-corruption and reform. If successful, it could derail Bangladesh’s democratic transition and set the country back economically and politically by decades.

Moving forward, political parties and civil society organizations must remain vigilant. As the consensus grows that the Awami League must not be allowed to rehabilitate through undemocratic means, it is equally vital that the private sector is protected from politically motivated targeting.

Economic prosperity and political stability are inherently linked. Undermining one to serve a hidden agenda jeopardizes the other. If Bangladesh is to maintain its forward trajectory, then unity is required not just in resisting political authoritarianism but also in safeguarding the economic engines that sustain its progress.

Many now argue that the real battle lies not in party politics, but in preserving the institutions that uphold democratic and economic integrity. A new One-Eleven must not be allowed to materialize—neither through tanks nor through twisted headlines.

Bd-pratidin English/ Jisan