What do we expect from progress? Happiness, of course. But development is not only about strangling rivers or clearing forests—it is also depriving citizens of happiness. According to Road Safety Foundation, 6,524 people lost their lives in road accidents over the past year. Some argue that this figure is inaccurate and that the actual number is even higher, as not all incidents are reported in the media.

It is essential to be hopeful, and those who encourage optimism may feel assured by the fact that a large consumer class has emerged in the country. This has increased the demand for goods in Bangladesh. And an increase in demand should logically lead to an increase in production. But does it? Is two plus two always four? If that were the case, we would have every reason to rejoice. Because an increase in production should mean more employment. But is that happening? Hasn’t the market already been flooded with foreign products? And haven’t many of the companies producing goods locally already passed into foreign ownership? Aren’t others waiting for the same fate? Most importantly, where is the profit from all this production and trade going? A large portion of it is being siphoned off abroad.

I know a businessman who is personally a gentleman and does not believe in capital flight. He wrote a book in which he cited the rise of the upper and middle classes in Bangladesh as evidence of the country's progress. Quoting an international bank, he optimistically stated that the growth of the middle class in Bangladesh would soon outpace that of Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, and India. Perhaps it will. But ordinary people like us do not have the courage to be thrilled by this prospect. Because such development would mean, on one hand, the looting of the country’s wealth and, on the other, a rise in unemployment and poverty. The wealthy are not only keeping their wealth abroad—they are also sending their children overseas. The number of students going abroad for education has been increasing rapidly. One newspaper reported that this stream has doubled in the past decade. At the same time, we also know that the number of foreign students coming to Bangladesh has steadily declined.

The cruel truth is, the more “progress” we achieve, the more patriotism declines. Does that mean love for the country has been entirely extinguished? Not at all. Patriotism still exists—especially among the disadvantaged. They do not even imagine living in another country. Most remain here. They work hard. And it is because of their labour that whatever progress the country has made has been possible. It is not the consumers, but the working class who are the real key to progress. Some among the disadvantaged go abroad, often by taking loans or selling land—not to settle, but to earn and send money back home. Many lead inhumane lives abroad, some end up in prison after being duped into illegal paths. Yet, they hold on to hope that their loved ones back home will be able to survive on their earnings. The rich, in contrast, only spread despair. They firmly believe this country has no future. And it is they who create this despair—especially through capital flight.

Take the current dollar crisis, for example, which has driven up prices across the board. The root cause is the conversion of local currency into dollars and the smuggling of funds abroad. Needless to say, this is the handiwork of the wealthy. They are the ones fuelling hopelessness, constantly reinforcing the belief that this country has no future. And this hopelessness is not confined to them—it spreads to others. Naturally so, for hopelessness is a disease—a contagious one.

In 1971, when we faced our gravest crisis and lived in constant fear of death, even in those dire times we did not despair. Because we knew none of us were alone—we were together, fighting together. But the signs of that unity breaking began to show as early as 16 December. And within a short time, it crumbled completely. The collective was lost, replaced by individual pursuits of progress or at least mere survival.

Why did this happen? Because what rose instead was looting, land grabbing, and the pursuit of personal gain. These became the dominant realities. In 1971, we were socialists; by 1972, socialism was on its way out, replaced by capitalism. And capitalism has since grown uninterrupted in Bangladesh. One government has been more capitalist than the last, and even when the same government remains in power, it gives greater concessions to capitalism with each term. But we did not fight the war just to clean roads for capitalism’s growth. Capitalism was already taking root under Pakistan. What we wanted was universal liberation—freedom for everyone.

People go abroad not only for education but also for treatment. Is Bangladesh lacking good doctors? Don’t we have modern equipment? Are we short of medical knowledge? No, we lack none of these. What we do lack is one thing: trust. Patients are unable to place their trust in local doctors. So those who can afford it go to Singapore or Bangkok; those who cannot try to go to India. And just like despair, distrust is also dangerously contagious.

Why is this trust lacking? Because most local doctors cannot give enough time or attention to patients. The reason is the constant pressure of earning more money looming over their shoulders. The more patients they see, the more they earn. There is more interest in income than in building a reputation for healing. Even our new health adviser has acknowledged this lack of trust. But can he restore it? It’s hard to believe he can. And even if he knows how, he likely doesn’t have the means to implement it. Because the problem is not with a few doctors or even the health system alone—it is spread across the entire state and society. Distrust prevails everywhere.

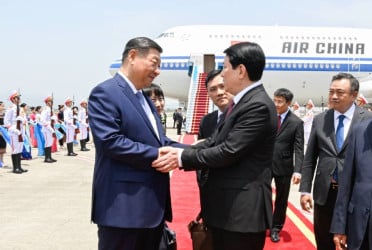

There’s now talk of shifting from India to China for medical services. Business-minded China is reportedly negotiating with the Bangladeshi government to set up hospitals for wealthy Bangladeshis, both in China and within Bangladesh. Meanwhile, just like past governments, the current one remains indifferent to developing public hospitals, which are the only option for the general public. The country has yet to have a government that truly stands by the poor.

But it all starts with a lack of faith in the country’s future. The privileged think this country has none. And so they turn away…

The writer is a professor emeritus at Dhaka University