After mass protests forced long-term Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to resign and flee the country in early August, Bangladesh found itself in a unique moment of opportunity to chart a path towards true democracy.

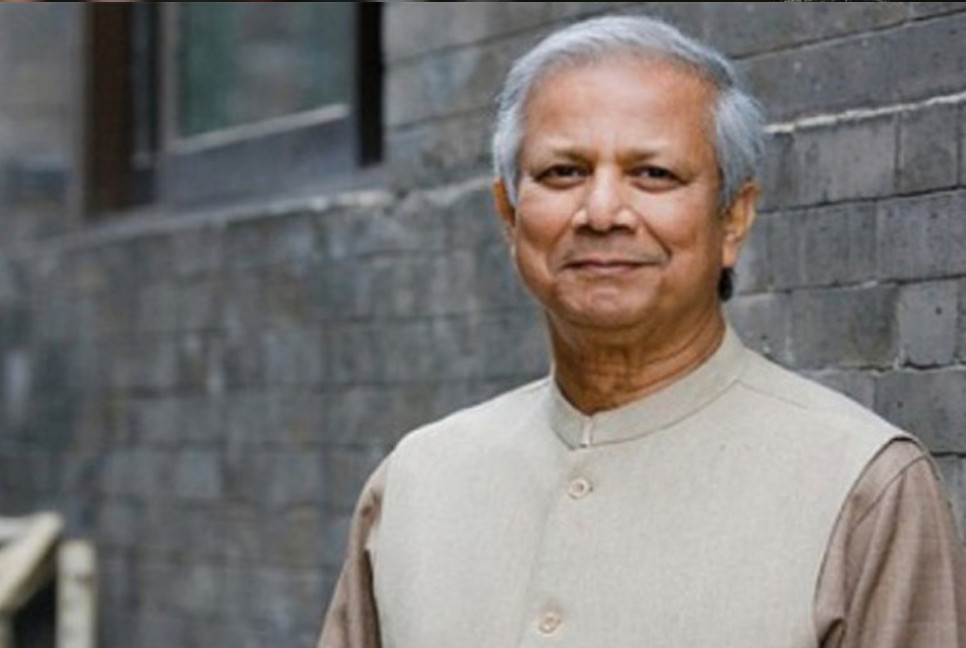

The interim government that was put in place to deal with the legacy of Hasina’s 15-year authoritarian rule is led by Nobel laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus and includes civil society leaders.

Yunus, a celebrated civil society activist, is well-equipped to lay the foundations for a new, truly democratic Bangladesh. He can draw on the experiences of Bangladeshi civil society to enable social cohesion and bring about a much-needed reckoning with the country’s tortured past. There are many ways in which he can protect and expand civic spaces. He can, for example, disband security units responsible for enforced disappearances and torture, reform the much-maligned NGO Affairs Bureau to ensure it supports civil society, or amend the Foreign Donations Law which creates a bureaucratic maze for civil society to receive international funding.

He should, however, act fast, as history tells us moments of opportunity and optimism like this can be fleeting. After a dictatorial regime is removed through revolution, democratic structures can fall prey to a rotation of elites. In the absence of a plan for what’s next, pro-democracy elements can be overwhelmed and derailed by fast-moving events.

In such scenarios, nationalist and authoritarian forces, who continue to hold power due to their alliances with the clergy and military, often fill the emerging power vacuum. At times, the military itself takes over. In other instances, leaders brought in as representatives of democratic forces turn to repression themselves to try and hold everything together.

In Sudan, for example, the 2019 overthrow of strongman President Omar al-Bashir was followed by several failed attempts at a democratic transition and eventually a military coup in 2021. Years later, civic space violations continue unabated and the country is still devastated by conflict.

In Pakistan, an initial military coup in 1958 supposedly aimed at creating space for a more stable democracy was followed by several decades of military rule and persistent attacks on civil society. Authorities in the country continue to silence dissent with crackdowns on activists, protesters, and journalists.

In Ethiopia, when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for finally securing a peace deal with Eritrea, hopes were high for regional peace and stability. Since then, however, he has presided over a bloody civil war in which mass atrocities were committed. The country is in turmoil, with human rights groups urging authorities to stop their crackdown on civic space and respect the rights of political opponents, journalists, and activists.

If Professor Yunus’s government fails to include civil society in decision making and shore up democratic institutions, post-Hasina Bangladesh can also fall into these pitfalls. But these are, of course, not the only possible scenarios. After a revolution, pro-democracy forces can also stay firm and enable the emergence of more complex, but also infinitely more positive, realities.

Sri Lanka, where widespread protests forced President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign and flee the country two years ago, is one example. Although things were far from perfect, a transition of power occurred through established systems of democracy in the country. Last month, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who ran on a promise of better governance and stability, won Sri Lanka’s presidential election.

Chile is another example of how democratic forces can persevere in the face of elite clawback. Despite significant resistance from establishment forces, Chile’s popular protests in 2019-2022 against economic inequality led to a series of reforms in education, healthcare and pensions. Guatemala, where in January the elected president was inaugurated despite repeated attempts by the old regime to scuttle a peaceful transfer of power, can also offer useful lessons for Bangladesh’s nascent government. In both these instances civil society groups played a key role.

While revolutions and popular uprisings did not produce civic utopias and perfect democracies in any of these countries, they also did not result in a return to square one.

Bangladesh’s interim government should pay attention to these examples where civic society secured important victories in difficult and complex circumstances. It should, however, also learn from cases where democratic forces failed to prevent the strongmen they helped topple from eventually being replaced by equally corrupt, anti-democratic leaders.

It is unrealistic to expect any new government to produce satisfactory reforms in all areas and a perfect democracy overnight, especially after decades of authoritarian rule. But countless examples around the world show that building a better future on the ruins left by long-term authoritarian leaders is possible – as long as the new leadership acts with determination, continues the dialogue with civil society, and remains on a democratic course.

If the interim government of Yunus gets it wrong, and the new leadership begins to try and stifle democratic dissent by suppressing civil society and clamping down on protests – whether these protests are by those who support the previous regime or others who are impatient for change – mistakes made during past transitions elsewhere might end up being repeated in Bangladesh.

But if Professor Yunus gets it right, draws from the successful experience of other countries, and lays the foundations for a robust democracy in Bangladesh, he could become a Mandela-like inspirational figure, and provide other countries in South Asia, where civic freedoms are widely repressed, with a regional example of a successful post-revolutionary transition. Many in the international community stand ready to support him.

Bangladesh is at a crossroads, and how Yunus and his advisors are able to navigate current political dynamics while respecting human rights and civic freedoms will determine the future of its democracy.

(The writer is the Chief of evidence and engagement and Representative to the United Nations at CIVICUS, the global civil society alliance)

Source: Al Jazeera

Bd-pratidin English/Lutful Hoque