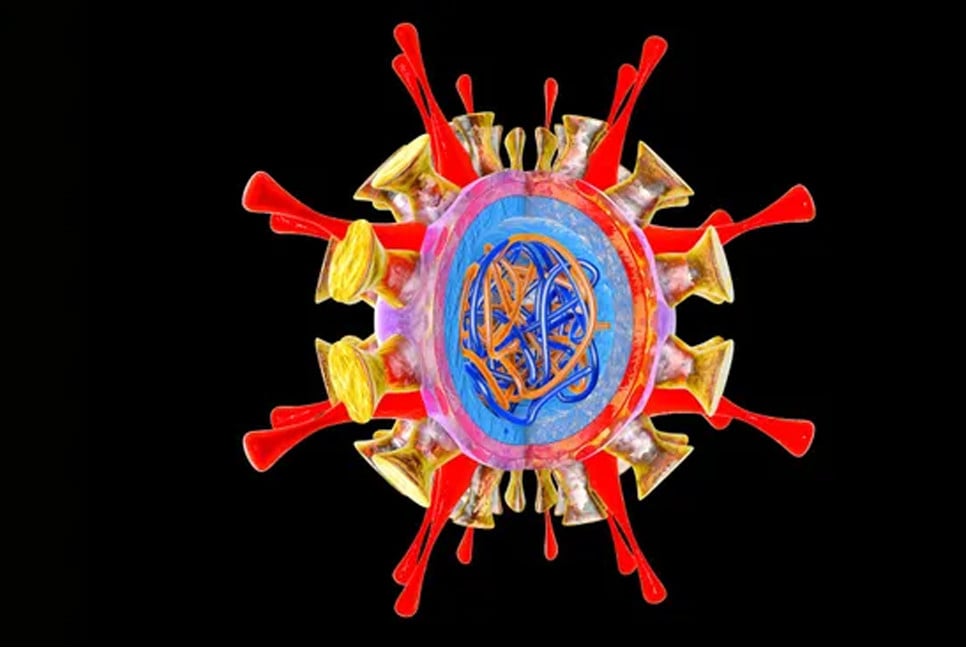

A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that H5N1 bird flu is improving its ability to spread between mammals. However, the virus still does not transmit as easily as seasonal flu.

H5N1 has been detected in at least 46 people in the U.S. this year, with cases so far resulting in only mild illnesses. While the CDC continues to assert that the virus poses minimal risk to the general public, researchers are investigating whether the avian virus has evolved to better infect mammals, as a precautionary measure.

H5N1 has been found in around 50 mammal species, including cattle. The key concern is how effectively the avian virus can infect mammals and how easily it spreads when it jumps to a new species, such as humans. Although no instances of human-to-human transmission have been detected in the ongoing outbreak, researchers are closely monitoring for any signs of such transmission.

In a new study published on October 28 in the journal Nature, the CDC used ferrets for their research, as the animals are susceptible to human influenza and exhibit symptoms similar to those seen in humans.

Seema Lakdawala, an influenza virologist at Emory University who was not involved in the study but collaborates with the CDC on other projects, explained, "Because they expel virus into the air, they have been used as a model system to study airborne transmission." She also pointed out that the lungs of humans and ferrets have a similar distribution of receptors that the virus can use to enter cells.

The study found that H5N1 can transmit easily between ferrets under certain conditions, indicating the possibility that the virus could spread between other mammals as well.

Troy Sutton, a veterinary researcher at Penn State who was not involved in the study, cautioned, "It doesn't mean that because the virus transmits in ferrets, it will transmit in humans." He clarified that the findings suggest the virus may be improving its ability to spread between mammals.

When scientists introduced H5N1 directly into the noses of ferrets, the animals developed severe symptoms, including diarrhea, breathing difficulties, and fever, with some even dying. In contrast, infections in humans in the U.S. have been relatively mild, with symptoms such as mild eye redness.

The CDC researchers utilized an H5N1 virus sample from a dairy farmworker in Texas, who was one of the first reported human cases of the virus this year.

According to Lakdawala, surveillance has not detected any additional human or mammal cases involving this mutation. However, the CDC has investigated its effects on ferrets in preparation for the possibility of it re-emerging.

One possible explanation, according to Sutton, is that researchers introduced millions of virus particles to the ferrets, a method that is standard practice in flu studies involving ferrets.

"It is probably higher than what a person would receive if they were exposed in a room to somebody with human influenza," Sutton said. However, he also noted that a milliliter of unpasteurized cow milk can carry 100 times more virus than what the ferrets were exposed to, suggesting that farmworkers may be at risk of higher doses of the virus.

Scientists are still unsure how farmworkers contract the virus. It could be through direct contact with animals, airborne transmission, or exposure to contaminated surfaces such as milking equipment. The CDC has investigated all three potential transmission routes in ferrets.

While the study offers valuable insight into the potential severity and transmission of H5N1, Lakdawala emphasized that it does not fully account for the complexities of the human immune system or human behavior. Additionally, such cage-based experiments do not address how the virus might spread over long or short distances. She stressed the importance of examining H5N1 viruses from other human patients to determine if the virus's behavior evolves alongside changes in its genetic makeup.

(Source: Livescience)

BD-Pratidin English/Mazdud